9/28 - Friday – Lunenburg to Annapolis Royal

Susie and Barry (our hosts) created a delightful breakfast for us – fruit salad, juice, tea, scones, quiche, bacon, toast, etc. The six proper guests (and us, the unproper ones) sat around a cozy dining table enjoying lovely food and lovely conversation while the gentle rain was falling quietly outside.

After breakfast we packed up and loaded the car, then walked to town to meet Eric Croft, a local guy known for his famous walking tours of Lunenburg. Come rain or shine, no matter what, he’d be there at 9 a.m. right down by the wharf to show the folks around town for $15 each. By the time we got to the wharf, it was starting to rain pretty hard. Bill didn’t want to stroll around town in this kind of weather. Optimistic me thought the skies would clear up – ha! I spotted a lone gentleman – it had to Eric Croft, the guide – who else would be out in weather like this? I dashed over to meet him and we were off. Bill reluctantly joined us, making it a threesome in the storm. From that point on, the weather only got worse. Torrential downpours and gale force winds battered us during the entire walking tour. Our umbrellas kept blowing inside out. However Eric was like a machine and went into “Stepford” guide mode. He had no rain gear, only a sweater. His heavily moosed hair kept its pointy peaks, but the raindrops collected on his head and then cascaded down each peak flooding his face. It didn’t take long for him to remove his glasses because the lenses were completely covered in water. He appeared irritated, but made no comments about the ungodly weather. Only one time did he show some evidence of humanness – that was when a couple of locals, standing in a covered garage, pointed and laughed at us. Eric did not want to be there. Bill was not a happy camper. It was a mistake I insisted we take such a tour. In spite of all this, I tried to “absorb” as much information as I could. Here’s some of what I learned.

Walking (in the Rain) Tour Facts

Lunenburg was established in 1753. The British signed up anyone who wanted land in the New World – Germans, Scots, French Protestants (not French Catholics), etc. All the new settlers had to do was pledge allegiance to the King of England. Almost all of the new settlers were farmers. When they arrived, they discovered the land was “un-farmable,” so they became fishermen or ship carpenters.

The town plan, hatched completely in England, was laid out on a grid. The planners didn’t realize that the town’s terrain was on a steep hill – one side sloping into the ocean, the other side into a river valley. (The only other town with the complete town grid still in tact is Savanna, Georgia.)

Foggy and drizzly Lunenburg |

Lunenburg, from a distance |

The houses were first built solid and square, using many ship construction techniques (e.g., ship knees for reinforcement). Many homes feature a distinctive architectural element that's known as the "Lunenburg bump" -- a five-sided dormer and bay window combo directly over the front door. When the town’s folk became more prosperous, they added Victorian gingerbread trim to their homes. Still later, they added indoor plumbing. For a time, they left the pipes exposed in the main hallway as a matter of pride.

Solid, early Lunenburg house |

Another square, solid home |

"Lunenburg bump" |

“Victorianized” |

The churches were established immediately because most of the settlers came as a result of religious persecution. There are five big churches in the little village. Two that stand out are St. John's Anglican Church and Zion Evangelical Lutheran Church (maybe because our granddaughter is named Zion).

St. John's Anglican Church was originally a simple New England meetinghouse style, built in 1754 of oak timbers shipped from Boston. Between 1840 and 1880, the church was remodeled and overlaid with ornamentation and shingles to create a "carpenter Gothic" style. On Halloween night of 2001, however, a fire nearly razed the place. In June of 2005, however, it reopened after a huge 3-year restoration project.

Zion Evangelical Lutheran Church (founded in 1772) has the tallest steeple and guided the sea captains journal home.

St. John's Anglican Church |

Zion Evangelical Lutheran Church |

The towns’ folk would graze their animals in the Town Square or common area. The town parades went from the square (Gazebo) to the waterfront. The street here was two times bigger than the other streets in town. A monument to Norwegians (I believe) is constructed in the town square.

Gazebo and common area |

Wide street for parades |

Because fish and lumber were so plentiful, the town became wealthy. At one time, one could walk across the harbor, jumping from one deck to another. Many fortunes were made from the sea. Carpenters, who specialized in the ornamental brackets that adorn dozens of homes here, also made fortunes.

Down by the wharf a monument (in the shape of a compass) commemorated all the locals who lost their lives at sea. (Sorry it was raining too hard to get the picture.) Many of the last names, listed on tall standing tablets, were the same. That’s because fathers and sons (and other family members) are usually on the same boat together when it goes down. Fishing is the most dangerous industry. The town is hoping never to fill up the last tablet in the monument with names. |

A couple of very wet hours later, the walking tour was over (and not a minute too soon for Eric and Bill). We paid our $30 and then sloshed off to the Fisheries Museum of the Atlantic in our squishy socks and soaked blue jeans. We spent about an hour at the museum leaving a trail of puddles. Here are some of the highlights that I recall.

Fisheries Museum of the Atlantic |

Love those colors! |

Fisheries Museum of the Atlantic – Fish we meet

Codfish made Lunenburg a wealthy settlement. The multitudes that once lived down deep in the ocean are gone now. However, we got to see some close up and personal, swimming around in a tank. They’re funny looking guys who have a hooked lip. They can’t see well. A thin line of sensors on each side of their body helps them navigate.

I was fascinated by one very weird looking spiny rockfish. The docent told me he had just been added to the tank. The new guy in the tank was still a little skittish.

Codfish |

The new guy in the tank |

We added to our lobster knowledge base. Nancy, a museum docent and wife of a local lobster fisherman, showed us a 14-year-old female lobster. We saw her long antennas and hair-like appendages that covered her body. She can’t see very well and needs them for sensing. Nancy then stroked the lobster on its back, and the lobster went limp. She loved it. Nancy said that backstroking is part of the lobster mating foreplay.

Lobsters lose their shells in a process that takes about 30 minutes. The shell splits up the back, and they emerge with their new soft shell. It takes the shell about 12 hours to harden up. At first, the new shells are too big for them – they need some room to grow. (Soft shell lobsters cost less because, with water trapped between the body and shell, there’s not as much meat per pound.) |

We met some other fish as well. (We could relate to them now because we felt like wet fish ourselves!) Next we went to a lecture on the Bluenose. Wendy was great at explaining the story – so we finally learned why Canadians revere their Bluenose.

Fisheries Museum of the Atlantic – Bluenose story

Schooners were big sailing vessels used for fishing. When the fishing was done, there was always some competition between schooners racing to see who could get to shore first. This friendly competition developed into an official cup-and-$4,000-prize-money-event. The Bluenose came to be known as the most famous of all the racing schooners.

Bluenose model |

Some of the trophies the Bluenose won |

Angus Walters, the captain and owner of the Bluenose, and William J. Roué, the ship’s designer, both lived in Lunenburg. The ship was launched in 1921 and didn’t even qualify for the first race, which was won by the Americans. The next year Bluenose was Canada’s entry and beat the Americans. Bluenose continued to win for the next ten years. The competition between the two was fierce (and even hostile). The Canadians were so proud of their Bluenose that the government issued a ten-cent coin and a 50-cent stamp with the image of the Bluenose

During WWII, with the focus on battleships and not sailing ships, the Bluenose was sold (with several other older vessels) and went to the Caribbean. There she sank. Years later, Schooner Brewery Company built Bluenose II, a replica of the original Bluenose. It took them only a few years to figure out how expensive it is to maintain such a boat, so they sold it to the government for a penny. The Bluenose now takes people on tours as a faded memory to the glory days of sailing. (The Bluenose II was parked a stone’s throw away from us at the museum.) |

Bill was tired of being wet so we walked back to our B&B to change into something dry. We had already checked out and no one was home. Being homeless, we walked across the street to the little library to dry off, change clothes and check our emails. (God bless libraries!)

Feeling better, we walked into town and lunched at the “Historic Grounds,” a cozy little café. We were happy with our shrimp pesto and dried tomato pizza. Lunenburg was foggy and drizzly and reminded me of the movie, “Shipping News.”

The Bluenose in the mist (Lunenburg wharf) |

More “Shipping News” scenes |

After lunch, we walked back to the Maritime Museum to explore the rest of the wonderful exhibits.

- We learned about the Rum Runners who made a lot of money supplying American with booze during prohibition. Honest fishermen gave up their hooks and lines to traffic illicit liquor to the United States and Canada. The exhibit told the exciting and dangerous stories using artifacts from the rumrunner boat, Reo II.

Rum Runners exhibit |

Items left from rum running days |

- A corner of one room was devoted to the Mi'kmaq (native people) with displays of pottery, weavings, codfish drying, etc.

- There was another room featuring whaling

techniques

and the enormous creatures themselves.

- The boat building shop gave me an insight into all the industries that produced items that were required for boat building and fishing – somebody’s got to package all the fish, somebody’s got to make the traps, somebody’s got to make a device that keeps a lobster from pinching – the list goes on and on

Lobster traps for sale |

Little wooden pegs to keep the lobster from pinching |

Boxes, barrels, crates (and labels) for packaging |

Dory loaded with goods |

- One area paid tribute to a local artist who was

afflicted

with polio and had to hold the paintbrush with his teeth.

The museum had several vessels docked outside, available for viewing. The weather was finally cooperating so the boats were open for tours. We visited the Cape Sable, a motorized, side trawler fishing vessel. It was built in 1962 and retired in 1982. The docent was very knowledgeable and so excited about showing off the Cape Sable, but I had seen enough.

Cape Sable

Cape Sable, docked outside the museum |

Cape Sable’s captain |

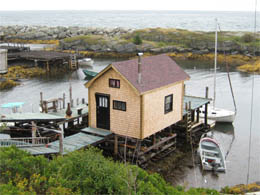

We walked back to the car at 2:30. The sun was trying to break through. We said “good-bye” to Lunenburg and drove down to Blue Rocks, a quaint fishing village built on, you guessed it, blue rocks. The rocks were very slippery, especially from the rain. I went down straight away, trying for the perfect shot. The strong winds were still whipping up big waves splashing over the blue rocks. It was an isolated place, without a hint of a tourist to be seen.

Do these rocks look blue to you? |

Town dock |

Eye popping colors |

House that looks like a kid’s drawing |

After a few photos, it was time to head to our final destination for the night -- Annapolis Royal . We drove through the breadbasket of Nova Scotia – gorgeous old farms – I still remember those red barns on the greenest pastures with a forest tucked here and there. Some of the leaves were just starting to turn colors. The falling yellow leaves floated down on the road – a perfect touch.

We stopped at Kejimkujik National Park at about 4:30. We had just enough time to visit the Indian dwelling established as a National Historic Site and then have a quick look at the Red Lake and Mills Waterfall.

Indian dwelling, Kejimkujik National Park |

Kejimkujik National Park |

The river runs through it |

Rushing water |

We got back on the road and arrived at our B&B (The Garrison Inn) at 6 p.m. The Garrison Inn is a classy place right in the heart of town, across from Fort Anne. Lucky for us, the manager had overbooked our room, so we were bumped up into a mighty fine room for just $89 – Life is good! We had a lovely gourmet dinner at the Inn – Lobster risotto and scallop kebobs. We are bad and wicked and loving this luxury!!!

The Garrison Inn |

Our Room |

9/29 - Saturday – Annapolis Royal

Lovely room, lovely breakfast at The Garrison Inn. The town crier stopped by our breakfast table. He was all decked out in his colonial attire to give me a peek at his shapely calves. (According to him, the style was knee-length pants so the guys could show off their legs and attract the ladies.) He announced that there was a Farmer’s Market in town this morning. Only wish I had my camera along – He was quite cute for a middle-aged guy.

Little town of Annapolis Royal

After breakfast we walked along the pier into town. Terrific little town and great views along the water.

Walk along the town pier |

From the pier |

Views across the water |

Views across the water |

Annapolis Royal Market

We made our way to the Saturday morning market. At the market we meet some artists / crafts people and bought a few souvenirs: a fish bowl and some earrings. Hooked rugs are the rage around here, but they do nothing for me.

The Quilt Lady |

The Jewelry Lady |

The Food |

The Pottery Lady |

Acadian family village -- Melanson Settlement

After the market, we drove to the Melanson Settlement, an Acadian family village. All that’s left now are mounds of earth ripe for archaeological digging. Charles Melanson and Marie Dugas married in 1664 and founded this little village on the banks of the Dauphin River (now called the Annapolis River). On the plateau or upland terraces, the Melansons and the other villagers built their houses, barns, orchards and gardens. Below, they built levies around the salt marshes, turning them into fertile farmland. Acadian dyke-land agriculture began in the Port-Royal area. The Acadians worked hard to construct a tide-gate system to block the salty tides from flowing back onto the land.

Melanson village was once here |

Four generations of families lived and prospered in the village. In December of 1755, the British rounded-up about 1,660 Acadians in this part of Nova Scotia. Everyone in this village was put aboard vessels bound for New England and North and South Carolina. Then the British, as standard operating procedures, burned the village to the ground.

Port Royal

Port Royal was a most fascinating place. It’s a National Historical Site and completely rebuilt detail by detail in 1938. The idea of preservation of historical sites started right here.

Entrance to Port Royal |

Coats of Arms over the entrance |

Port Royal – outside the walls |

Inside the courtyard |

Courtyard |

More scenes inside the fort |

John, dressed in period costume, greeted us. He had just gathered some herbs from the garden for drying. Ranger Judy, a Mi’kmaq Indian, told us so much about this place and about her native heritage. When she was a poor little girl, she played in the mud, making “mud cakes.” She ended up with pinworms. Her father, with his tribal wisdom, knew what to do. He took the quills from a porcupine and brewed a tea. That cured her. Judy said she was sorry she didn’t learn more about the medicine her father concocted.

John and his herbs |

Ranger Judy looks at a buckskin painted by the Mi’kmaqs |

Judy took us from room to room and showed us where the settlers slept, where they worshipped, where they built boats, where they stored their furs and supplies. It was absolutely fascinating. Here’s just some of the things we learned about this early settlement.

Port Royal – A Little Background

Port Royal was the first European settlement in North America, founded in 1605 by Pierre Dugua Sieur deMons and Samuel de Champlain. Samuel de Champlain was a famous explorer and mapmaker. He was also the designer and architect of this French fur-trading colony.

In 1603, Sieur de Mons received a fur trading monopoly in the new world on the condition that he would establish a colony there. On his first expedition in 1604, he selected the site. That winter nearly half of his men succumbed to cold and scurvy. They developed sores and then their teeth fell out. The Mi’kmaq Indians showed them how to survive.

The Mi’kmaqs had a long lifespan – 80 to 100 years. The French only lived into their 40’s. The Mi’kmaqs were tall and strong; the French were small and puny. In spite of their different goals and backgrounds, they all got along fabulously and formed a strong alliance against the British who came later to conquer and destroy.

Membertou was a respected chief of the Mi’kmaq Indians living along the south shore of the Bay of Fundy. He was also a great warrior and famous shaman. When the French arrived in 1605, he and his family converted to Christianity. On June 24, 1610, he was baptized in the chapel, making him the first native chief to be baptized in Canada. He was 100 years old at the time and over six feet tall. It must have been quite a sight with the little French priest. He helped the French establish the Port Royal settlement and traded furs with them for European goods. A year after his baptism, he died (September 18, 1611). After his death, the alliance he built with the French lived on for more than a century.

Chapel where the chief was baptized |

Sieur de Mons (the owner of the company and governor), Samuel de Champlain (architect), the priest and Lescarbot (colony writer / poet) each had their own quarters. There was a dining hall, a chapel, kitchen, drug store, blacksmith’s shop, sleeping areas and common areas for the men.

Drug Store |

Governors quarters (Judy says it’s haunted) |

Herb mixing items |

Kitchen |

Dining room |

Storage room for furs |

The men were sea captains, shipbuilders, carpenters, fur trappers, farmers, blacksmiths, cooks, etc. Each year, fifty French guys were sent to Port Royal to work in the colony for one year. (Women were expected to come later, but the colony shut down and they never came.) The men were paid well. In the spring, a ship from France came to pick them up and drop off supplies and new men in the colony for the next year. The ship also carried back all the beaver pelts in the fur trading business. Beavers, lumber and fish were plentiful. All they had to do was gather up lobsters off the beach after the tide went out.

The French weren’t allowed to marry the Mi’kmaq women. That was not a problem for the Mi’kmaq women because they said the French were smelly bears with hairy beards.

Business was great – beaver hats were all the rage in Europe. The pelts were sent back to Europe to harvest the soft fur that is under the “guard fur.” This soft fur was clipped and matted on the hats. Later, the hat manufacturers used mercury to mix in with the matting material. Many of the “hatters” went mad because mercury makes one crazy – thus the term, “Mad as a hatter.” Fashions changed and fur hats weren’t in – so naturally the fur-trading business dried up.

NOTE: Judy told me that beavers are very destructive animals and that they must destroy in order to survive. They must constantly eat and chop or their teeth will get too big and then they can’t close their mouth – which means death to the beaver.

Historians know so much about “New France” because of the colony’s resident writer, Lescarbot. He wrote about day-to-day life in Port Royal and his documents were shipped back to France each year and archived. He wrote about the Mi’kmaq Indians who hung out around the fort. He talked about the playful Mi’kmaq children running through his room and knocking his desk while he was trying to write. He wrote poems and produced a play “The Theatre of Neptune” for the supply ship that came in each year. (The colonists were the actors in his play.)

Samuel de Champlain must have been quite a guy. He introduced the “Order of Good Cheer” to “keep our table joyous and well provided.” Prominent members of the colony took turns serving up a banquet and arranging after-dinner entertainment. They had processions carrying platters of food into the dining room. It must have been quite a place. (French are still big on food and presentation.)

Dining room and Order of Good Cheer |

Port Royal survived and thrived until 1613, when it was destroyed in an attack by Captain Samuel Argall of Virginia, under British orders.

|

Ranger Judy filled our heads with facts. We loved the place, but had to move on – lots more to do and see on today’s agenda.

Fundy Coast – Delaps and Parker’s Cover

We drove down a gravel road to Delaps to view the rugged Fundy Coast. Delaps was a dilapidated fishing village. I snapped a few photos of the coastline and cobblestone beach and then we drove to Parker’s Cover for more Fundy Coast.

Fundy Coastline |

Cobblestone beach |

The fun in Fundy was over when we drove back towards Annapolis Royal. We stopped at the Visitor’s Center. The Tidal Power Station exhibit was on the second floor of the Visitor’s Center, with views of the power station down below.

Tidal Power Station

I was hungry and overwhelmed by all the models and displays explaining the Tidal Power Station. I did get that this is the first and only tidal power plant in North America. Since the Bay of Fundy has the highest tides in the world (average tide of 7 meters), this is the perfect spot to put those tides to work.

Bill said it was an experimental thing. All they did was dig a HUGE hole where the tide goes over the generator. The tides going in and out turns the generator – simple enough … And this generates electricity for about 4,500 homes. Great, with that done, we could now go to lunch!

Visitor’s Center and Tidal Power Station Museum |

A really big hole out there! |

We drove back to Annapolis Royal and had a $2.95 burger with the locals at Fort Anne Café. It hit the spot and gave us the strength to go on to our next stop. Fort Anne National Historic Site right across the street from our B&B.

Fort Anne Café |

Streets of Annapolis Royal |

More street scenes |

Main Street |

Fort Anne National Historic Site

Fort Anne was situated on steep, grassy hills with rivers flowing below. Over 3,000 years ago the Mi’kmaq Indians stopped here on their voyages.

Fort Anne tucked below grassy mounds |

Fort Anne – front entrance |

In the 1600s and 1700s, the site was the center of early European colonies. French called the place Acadia and the British called it Nova Scotia. (We all know who won.) Britain and France built forts to defend and protect their settlements and advance their empire. On this strategic site they built Fort Anne, Canada’s most attacked fort and oldest national historic site.

NOTE: Besides the British and French, the Scottish also came to Nova Scotia. A group of about 70 Scottish settlers began a colony here in 1629 eight years after King James I issued a grant to Sir William Alexander. It was Sir William’s son who brought the Scots here to establish a colony. They built a small fort, called Charles Fort, which now lies beneath Fort Anne. Many of the Scottish settlers died during the first winter, but those who survived (thanks to the Mi’kmaq) thrived on agriculture, fishing and trade. The Scottish colonization was short-lived. In spite of that, Nova Scotia owes its name (Nova Scotia means New Scotland), flag and coat of arms to this early settlement.

The museum was filled with stories of the continual attacks, defeats, hand over the keys, build a bigger, better fort. There were stories of how the Mi’kmaqs fought side by side with the French in order to defeat the feared British. (It didn’t work.)

We walked around the earthen walls lined with canons pointing outward. We visited the only surviving building from the French period. Built in 1708, the “Powder Magazine” was used to store the fort’s gunpowder. (I suppose it survived because it had to be strong.) On that beautiful day strolling through the fort, I wondered about all the dead bodies we were stepping over.

Powder Magazine |

Canon pointed outward |

Climbing on the earthen walls |

View from the walls of Fort Anne |

Manic travelers that we are -- we had time for just one more adventure that day. We wanted to learn more about the Native Canadians (Mi’kmaq) and Bear River First Nation Heritage and Cultural Center seemed just the place to start.

It took 45 minutes to drive to our destination, some of it along the Evangeline Trail. We were treated to more eye-popping scenes – rolling hills, vineyards, green pastures dotted with forests just starting to show their fall colors. The farmhouses and barns were perfectly placed on the landscape.

We sped through the little town of Bear Lake and missed the sign to the Reservation (assuming there was a sign). Finally, we stopped and I asked a farm gal for directions. (Our GPS navigator, A.K.A. “The Bitch,” was of no use – She didn’t have a clue where this Indian Culture Center was.) With real human input, we retraced our steps to town and turned by the Fire station. A few more miles and a few more confusing signs – then we had arrived.

Bear River First Nation Heritage and Cultural Center

We paid our money and entered the odd museum. It looked like a high school gym with a stage at the end. The eight or nine display boards were nicely done. I learned about canoes, wigwams, respect for nature, and so on.

After we finished perusing the exhibits, we took the loop trail out back to learn about medicinal plants. The trail was once used for hunting and later as a logging road. The trail signs were bad and most of the plants were dead. We saw a few constructed teepees, fire

ring

and a crumbling old cabin. We got lost – what a clever way for the Mi’kmaqs to get back at us white European types. We finally found a clearing that led us back to the packing lot.

Mi’kmaq Birch canoe |

Nature trail |

Nancy in the wigwam |

Bill by log cabin |

NOTE: Mi’kmaqs have the same history as our Native Americans south of the border – Help the settlers through the dreadful winters, show them how to plant, fish, survive. And what does that get you? Environment destroyed. Food supply gone. Promises broken. Death from white man’s diseases. And finally, your way of life destroyed. Pretty depressing.

It was 5 pm. We stopped in the little run-down town of Bear Lake only to find that most of the places were closed. One funky store had cool sayings painted on the walls. (My favorite was: Don’t criticize what you can’t understand.)

Little town of Bear Lake |

Funky store in Bear Lake |

We saw a few teens hanging out trying to figure out how to have a little fun on a Saturday night. After peeking into a few store windows, we decided to go back to our Inn in Annapolis Royal. GPS lady, “The Bitch,” wanted us to take the freeway and I wanted more quaint back roads, rolling hills and view of the lakes.

We got back to our room and regrouped for our evening of entertainment. We walked into town. We wanted to eat at Newman’s, but it was closed, and for sale. We ended up at the Ole Towne Pub for a beer and some grub. I took a risk and had the Thai Chicken – good choice. I didn’t realize it, but I was missing chicken and something spicy. Bill had split pea soup and a turkey sandwich. (Mine was better.)

After dinner we walked through the town (for the last time) and then on the Pier. Lovely evening. We walked past Fort Anne and caught the last views of the Old Burying Ground before sunset. We just had to cross the street and we were home!

Old Burying Ground |

Sunset (from the town wharf) |

9/30 - Sunday – Annapolis Royal to Amherst

We had a nice breakfast at the Garrison Inn and were on the road by 9. We drove along the Evangeline scenic route. (Bill wanted to drive an extra 20 miles to a park to take a 4-mile hike. I wanted to see more along the way. We later learned that the park was closed for the season. I was relieved.)

NOTE: We’re amazed at how environmentally conscious Nova Scotia is. Everyone here has learned to be recycling fanatics. We have to study each piece of trash to determine if it was for “organics,” “redeemable,” “recyclables” or “misc. - other garbage” and then toss it into the appropriate bend. U.S. has a long way to go to come close to Canada’s high standards for protecting the environment. Once again, I’m sad we’ve lost our way.

At 11:30 we stopped in Wolfville at the Visitor’s Center. The cutest gal (very Valley girl-like) helped us. She told us to take a look at the harbor. The tide is way out now. The “tidal bore” (when high tide comes in with such force that it creates a wave) will be around 2:00PM. We drove over to check it out, and there it was, a huge mud pit. There wouldn’t be anything special about it with high tide – just another harbor filled with water. These tides really go out!

Tide is out leaving an empty harbor |

Nothing but mud |

We walked through Wolfville and ended up at Acadia University, founded in 1838. There were signs on the campus announcing a “Walk the World for Schizophrenia” and a rally was the happening thing at the stadium across the street. Loud speakers were blasting out the song “Y-M-C-A” – loud enough to stick in my mind for the next couple of hours.

Acadia University |

Hallowed halls |

Our Valley-Girl-Visitor-Center-guide told us where to get the biggest, best and cheapest sub in town, so we found the grungy little student hole-in-the-wall and stuffed ourselves by splitting an Italian sub for $5. Because it was Sunday, most of the shops in town were closed, so we headed down the road to Grand-Pré .

Grand-Pré National Historic Site of Canada is a beautifully done park that tells the story of this area, which was the center of Acadian settlement from 1682 to 1755. The sad ending began in 1755 (and ended in 1762) when the British deported the Acadians and then burned their village.

Grand-Pré is French for large meadow or Grand Prairie. It was a wonderful historical site and the best orientation film we ever saw – a flashy multi-screen production with a very informative script. At times 3-D laser-like characters would appear on stage commenting on the film. The meadows were grand and green and the displays left us awestruck.

Grand-Pré National Historic Site |

Bill helps himself to an apple on the grounds |

Acadian Mother and Father on the grounds |

Nancy joins the family of statues |

Grand-Pre – A little history

In mid-17th century, a group of Europeans, mostly from France, came to the New World, (referred to as Acadia – later became Nova Scotia) to establish a French colony. The children of these settlers came to be known as Acadians.

NOTE: Most

Acadians

are descended from about 50 French families who settled Acadia, mostly in this area around Port-Royal, between 1636 and 1650’s. They formed the roots of the Acadian people and within a few generations, considered themselves a distinct people – Acadians and

Acadiannes– settlers of Acadia.

The site, Grand-Pré, on the shores of the Minas Basin, was first settled around 1680 when Pierre Melanson dit La Verdure, his wife Marguerite Mius d'Entremont and their five young children left Port-Royal to make a new home. (Port-Royal, the place we visited yesterday, was then the capital of the European colony.) The British soldiers and the French soldiers (with support of the Mi’kmaqs) were constantly battling over control for this strategic fort – not a healthy place to raise a family.

Other families joined Melanson at Grand-Pré. As a community, they worked hard building dykes to hold back the tides along the basin, reclaiming the land from the sea. The dykes changed the tidal marshlands into rich pastures for their animals and fertile fields for their crops. Within four generations, the Acadians had built a very prosperous community and Grand-Pré became the bread basket of the New World. It wasn’t long until Grand-Pré outgrew Port-Royal in population. By the mid-18th century Grand-Pré was the largest of the many Acadian communities around the Bay of Fundy and the coastline of Nova Scotia.

In the backdrop, the British were claiming land and battling the French all around, leaving these dyke builders and farmers caught in the middle. The British began winning more and more battles and then basically won the war in 1713. Under the treaty of Utrecht, Acadia became Nova Scotia and the Acadians became British subjects.

The Acadians were permitted to remain Catholic and stay on their land, but they had to live under British rule. They were asked to take an oath of allegiance to the British crown, but many refused to sign the oath.

Things came to a head in 1744 when England and France once again declared war. The French from Québec and from their fortress in Louisbourg tried to retake Acadia. There were attacks and counter attacks. Halifax became the new capital of the colony in 1749. The majority of those living in this British colony were Acadians (French Catholics). The governing British didn’t like the fact that the Acadian numbers were growing and they lived on the richest farmland. The British wanted to stop this and encourage more Protestant settlers to come to the area.

1755 was an important turning point when the British confiscated the Acadians’ boats and their guns. The French Fort Beausejour was also captured and Acadian delegates in Halifax (the new British capital) were thrown in prison.

The governor, Charles Lawrence, decided to settle the Acadian question once and for all. Concerned for the colony's security, Lawrence demanded that the Acadians take an unconditional oath, which meant they would fight under the British flag and fight against the French forces. The Acadians refused and remained loyal to their French heritage. That was just too much. The British decided to expel the Acadians from Nova Scotia and relocate them among the British colonies to the south, from Massachusetts to Georgia or back to France. On August 19, 1755, Lieutenant Colonel John Winslow, with his British Colonial troops from New England, arrived in Grand-Pré to do the dirty work. They marched to the town and set up headquarters in the church.

At 3 p.m., on September 5, 1755, 418 Acadian men and boys (ten years and older) are ordered to attend a meeting in Saint-Charles Church. It was there Winslow informed them that they and their families were to be deported. He also announced that their land, livestock and properties were now owned by the Queen.

Replica of Saint-Charles Church |

Building the church, 1922 |

Shock and dismay rang through the church. Immediately afterward, all 418 men and boys were imprisoned in the church. Five days later, approximately 200 detainees were marched to five ships anchored in the Minas Basin. The women, children and elderly were rounded up and marched on board the ships as well. Many were separated from their families. There were six more weeks of imprisonment before the departures began in late October. Before they departed, the Acadians watched in horror as the British troops burned their settlement to the ground.

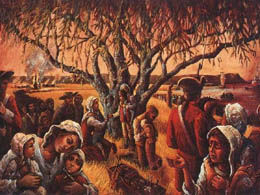

Deportation Day |

Saying good-bye to their homes |

Over 2,200 were deported from Grand-Pré, over half of them children. Many died, a few escaped. The majority set sail on a terrible voyage to the British colonies in America (from Massachusetts to Georgia) and some were sent back to France.

After a long journey the battered and poor Acadians who managed to survive landed at their destination and had to start all over again. They were cursed and unwelcome because they were Catholic and immigrants. Many of the children, in order to survive, had to become servants to the wealthy colonists – an awful fate.

Between 1755 and 1763, British forces deported approximately 10,000 Acadians not only from the Minas Basin area, but also from all of Nova Scotia. The deportation ended in 1763 when England and France once again made peace. In 1764 the British government of Nova Scotia permitted the Acadians to return to the colony on the condition they settle in small groups and in isolated areas of the peninsula.

After ten long years, some of the Acadians returned to their homeland. However, they were unable to settle on their ancestral lands because the government had granted that land, for free, to English settlers. |

Henry Wadsworth Longfellow was the one who put Grand-Pré on the map. Forgotten for almost a century, he wrote his famous epic poem, Evangeline, A Tale of

Acadia. It was about a fictional Acadian maiden who was part of the tragic deportation of the Acadians by the British. Evangeline and her lover, Gabriel, were separated during the deportation. Evangeline ended up in America spending years searching for Gabriel. She finally settled in Philadelphia and, as an old woman, worked as a nurse among the poor. While taking care of the dying during an epidemic she finds Gabriel among the sick, and he dies in her arms.

Excerpt - Evangeline, A Tale of Acadie - Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, 1847

"THIS is the forest primeval. The murmuring pines and the hemlocks, the twilight,

Stand like Druids of eld, with voices sad and prophetic,

Stand like harpers hoar, with beards that rest on their bosoms.

Loud from its rocky caverns, the deep-voiced neighboring ocean

Speaks, and in accents disconsolate answers the wail of the forest.

This is the forest primeval; but where are the hearts that beneath it

Leaped like the roe, when he hears in the woodland the voice of the huntsman?

Where is the thatch-roofed village, the home of Acadian farmers " |

Evangeline, published in 1847, about a hundred years after the deportation, brought the world’s attention on the great uprooting of the Acadian people. Because of this epic poem, American tourists wanted to visit the birthplace of Evangeline. However, nothing remained of Grand-Pré, the original village, except for the dykelands and a row of old willows.

Sixty years later, in 1907, John Frederic Herbin, poet, historian, and jeweler, whose mother was Acadian, bought the land believed to be the site of the church of Saint-Charles so that it might be protected. He sold the property to the Dominion Atlantic Railway (DAR) in 1917 on the condition that Acadians’ settlement be preserved. The DAR put a railway line to the site.

In 1920 the DAR erected a statue of Evangeline. The statue was a lovely creation conceived by Canadian sculptor Philippe Hébert. After his death, his son, Henri, completed the sculpture. One of Henri’s sisters, Pauline, posed for the face. The face shows Evangeline crying for the lost land.

Statue of Evangeline with church in the background |

Statue of Evangeline |

In 1922, a committee raised funds to build a memorial church in Grand-Pré. The interior of the church was finished in 1930, the 175th anniversary of the Deportation, and the church opened as a museum. We went inside the church to see the stain glass windows depicting the deportation. We also saw the cat, named Evangeline, sleeping in the window.

Church murals |

Evangeline, all curled up |

We left with our heads filled with facts and our hearts filled with emotions. We were hoping to get down the road to our next adventure -- to catch the Tidal Bore in the town of Truro. Truro claims the biggest tide anywhere in the world – and today was supposed to be especially high because of the moon’s position. For a fee, of course, you can float in big rafts with the tidal bore. (Bill referred to it as the “total bore.”)

Bill wanted to take the coastal route, but I wanted to dash through country scenes, hoping to save some time and catch the big waves at Truro. (Of course, “The Bitch” wanted to hit the freeway full speed ahead.) We ended up in the country, driving through gorgeous, homespun farm scenes peppered with cattle. This was the fist time we saw herds of cattle.

After an hour of driving, at 4:30, we arrived at the “new, Wal-Mart strip mall style” Truro Visitor’s Center (called Gooseneck). Gooseneck is the Mi’kmaqs’ king of nature. In front of the Visitor’s center stood a tribute to “Gooseneck,” a tacky 20-foot statue of an Indian guy holding a tomahawk. It was a sight for sore eyes – only wished I had snapped a photo. We dashed into the center only to learn that the big tidal bore was at 3:17 today – We had only missed it by 45 minutes.

Truro was butt ugly and we had seen enough at the Visitor’s Center so we drove on to our final destination, Amherst, another hour down the road. This time, “The Bitch” was happy because we headed for the freeway, just her style.

“The Bitch” came in handy in finding our way to sleeping quarters. Nobody was home at our first choice (Tureen B&B). Second choice, Victoria Motel, was the worst, smelliest place he’d ever seen (even worst than places in the third world countries where we frequent). Luckily we got the last room in a lovely Victorian B&B (Brown’s B&B). Nancy (the host) had grown up in the house. She was so friendly while poor Dean (her husband) tried to stay tucked away.

Brown’s B&B |

Our cozy room |

We unpacked and walked a few blocks into town. It’s a shabby old town, a little rough around the edges – it’s definitely not touristy. We stopped in at “Duncan’s Pub” for our beer. It was comfy and cozy, but after 20 minutes and still no one to take out order, the charm was gone. We walked down the street to “Cinder’s,” billed as a steakhouse. The waitress was very ditsy, but we coached her through the ordering process and ended up happy with our beer and our nice chicken / fresh tomato pasta dish.

Amherst Courthouse |

Mural painted on a 5-story building |

Funky statue in the town square |

Another funky statue in the town square |

We walked back to Brown’s B&B. Nancy and Dean were in the living room with some guests they had known for years. The guests, from Florida, were showing videos of their cottage in Cape Breton. Nancy invited us in to join them. Luckily, they were at the end of the show. The couple was sweet. They had built this rustic cottage 35 years ago and come back every year.

We went up to our room to shower and wind down. It was then that I thought that the room was haunted. The door opened by itself. Bill was in the shower down the hall – I hoped that he would come back soon!

10/1 - Monday – Amherst, Nova Scotia to Bangor, Maine

Nancy, owner of our B&B, had breakfast for us. I picked out all the bananas and kiwi in our individual fruit bowls and snuck them into Bill’s bowl. Everything else was too sweet for our tastes – cinnamon rolls and three choices of sugar frosted cereal. In spite of our disappointing breakfast, we enjoyed our stay.

It was mostly a driving day with our goal to get to Bangor. With such a clear goal, we relinquished our control over “The Bitch” and let her take charge – a real mistake. We had to travel ten miles out of the way and get her straightened out. Finally, we drove across the border from Nova Scotia to New Brunswick and then got gas. The gas is cheaper in New Brunswick and there are fewer taxes. We drove south through New Brunswick, stopping at a Visitor’s Center, desperately looking for a t-shirt for Terry (no luck).

Lunchtime came. Bill remembered the Subway Sandwich place we had eaten at two weeks ago. (Don’t know how he does that – I’m totally direction-less.) We shared a sandwich and spent the last of our loonies on three chocolate chip cookies for the road.

There was a long line at the border heading to the U.S. (from St. Stephen into Calais, ME). In Calais, we stopped at the Visitor’s Center to get directions to the Moosehorn Wildlife Refuge -- a refuge and breeding ground for migratory birds and other wildlife, located just off Route 1. The preserve was established in 1937 by FDR and funded by issuing Duck stamps.

The area was once a booming place because of the huge logging industry in the 1800's. Fifty miles of old logging roads are closed to traffic, but open for hikers. We took a three-mile hike through the preserve, hoping to finally see some moose, but no such luck. We would go home moose-less. The trail took us through some forests, some swampland and some wetlands. It was the first day of hurting season – always a bit of concern. The landscape wasn’t that spectacular, but the walk gave us a nice break from the drive.

Hiking down an old logging road |

Swampland |

Look what logging can do to a place |

A touch of beauty |

“The Bitch” got us to the downtown Bangor Library where we checked our email (probably on a computer donated by Stephen King – Bangor’s

favorite

native son.

He’s given a lot of money to the community.)

Based on the limited description of Stephen King’s home in our guidebook, we were able to find the strange place with not much effort. I dashed out of the car with my camera hurriedly capturing the house in last of the sun’s ray. Bill remained in the car, embarrassed by my star-struck behavior. The house was a hoot – exactly like one you’d find in his books, with bats decorating his iron gates. I don’t read his novels, but I am a big fan of his. I read his book called “On Writing,” intended to pass along his wisdom to writers. I was charmed by the book and found it to be a very honest autobiography. Posted in his front yard was the sign, “Support the Troops – Bring them home.” I’m even a bigger fan of his now.

Stephen King’s home |

While I was snapping away, a woman in her thirties, with a little boy who looked to be five or six, approached me. With a twinkle in her eye, she said, “You might just catch him walking his dog.” All I could say was, “Do you think so?” I thought she was just a neighbor. I quickly changed my mind when I saw her and the little boy walk up the driveway and into Stephen King’s house. (They may have been Stephen King’s daughter and grandson.) How I wished I had chatted with them just a little. I jumped into the car and Bill and I took off in the car looking for anyone with a dog – but no such luck – dog gone it!

We settled down from our almost-brush-with-greatness and checked into the Super 8 motel, probably the best Super 8 we’ve stay at.

We went to dinner at Sea Dog’s Brewery down by Bangor’s wharf. The local brew was good and cheap and the dinner (chicken and cream cheese pizza with Caesar salad) hit the spot.

We went back to our motel. Bill went to the car to quietly disassembly “The Bitch” and to have a few quiet moments with her. I know he cares for her more than he can admit.

Last night with “The Bitch” |

Super 8 in Bangor |

10/2 -- Tuesday – Home, Sweet Home

We had a 9:30 a.m. flight from Bangor to Boston – then a 4:30 p.m. flight from Boston home. The Bangor airport was abuzz with young army men and women headed off to Iraq. They were all polished and coiffed. The USO volunteers were there with goodies and well wishes. The troops loaded onto the plane and were ready to take off when a couple of them were missing. The load speakers called their names while the airport personal went into panic mode. Finally, the last two came running down to the loading area. (Wonder what their story was.)

We arrived in Boston around 10:30 a.m. and then had to wait another 5 plus hours for our flight to San Diego. I read a book on explorers that I bought at the airport’s “Museum store.” I found it fascinating. I noticed Bill taking “The Bitch” out her box and reading her manual.

The 6-hour flight to San Diego was uneventful – just like we like it! We arrived on time about 7:30 p.m. Amy picked us and took us home. (Brian was away on business.) It was great to see Amy and little toothless Zi (who had grown quite a bit).

We were glad to be home and happy to have shared another wonderful adventure together!

Postscript

It was great to spend three weeks with my buddy. “The Bitch” was our third passenger and at times, the third wheel. With the details filed away, time to take a breath and see “the forest.”

- Only 2 and a half days of rain out of 21 days.

- We drove 2,300 miles.

- Didn’t see a moose.

- Saw picture-perfect scenes, one after another. The best were drenched in glowing morning light or in the evening’s long shadows.

- The landscape was not cluttered with people, freeways and cars – The harsh winters saved this haven from population explosion.

- Met real people – solid, grounded – some a little too solid (from a diet of fish and chips!).

- Learned a lot about the world of lobsters, cod fish and salmon.

US and Canada share a similar history – lots of bloodshed. Leaders stepped over dead bodies to get to the top. (Sometimes we were walking on wall-to-wall unmarked graves.) The British were aggressive and mean, but are now witty, charming and don’t grab land. Land grabbing is now all about oil – and soon will be about water.

Canada may be the focus of the next land grab – they have lots of oil, and lots and lots of water and their loony (dollar) is strong. Canadian underdogs are no more.

The true survivors are the wildflowers and the apple trees. Some of the apple trees, a little gnarly and bent, were planted in settlements over 150 years ago and still provide apples for those of us within reach.

Canadian Visitor Centers and Public Libraries (with Internet access) were our connection to home. The emotional / social needs of connecting with friends and family are as strong and real as our physical needs.

We consider ourselves lucky to have explored this landscape and learned about the history and people that have made this place even more special (e.g., Alexander G. Bell, FDR, Lucy Maud Montgomery, and Stephen King).

We meet characters everywhere:

- The Cheticamp “hooker” (as in hooking rugs) married to the town barber – my life had I not been born in the land of opportunity.

- Salmon Lady and her distaste for seals – “nothing but rats on water”

- Sierra – Ranger at Acadia National part – with spunk and spirit

- Betty, crusty wife of a lobster fisherman

- Brenda (from Halifax), who popped into our life a couple of times on the road – was there to show us around – and make us feel at home.

- Bob and Aldine shared their home (in Charlottetown ) as if we were relatives

- Ron and Marg -- more wonderful “relatives” in Halifax / Dartmouth – with their five daughters all named “Mary” – Marg voted “Best Cook” in all of Canada

|